StoryBuilder-Manual

Creating a Story pt 9

We know how our story starts and how it ends; we’re left with the middle story that ties these two parts together.

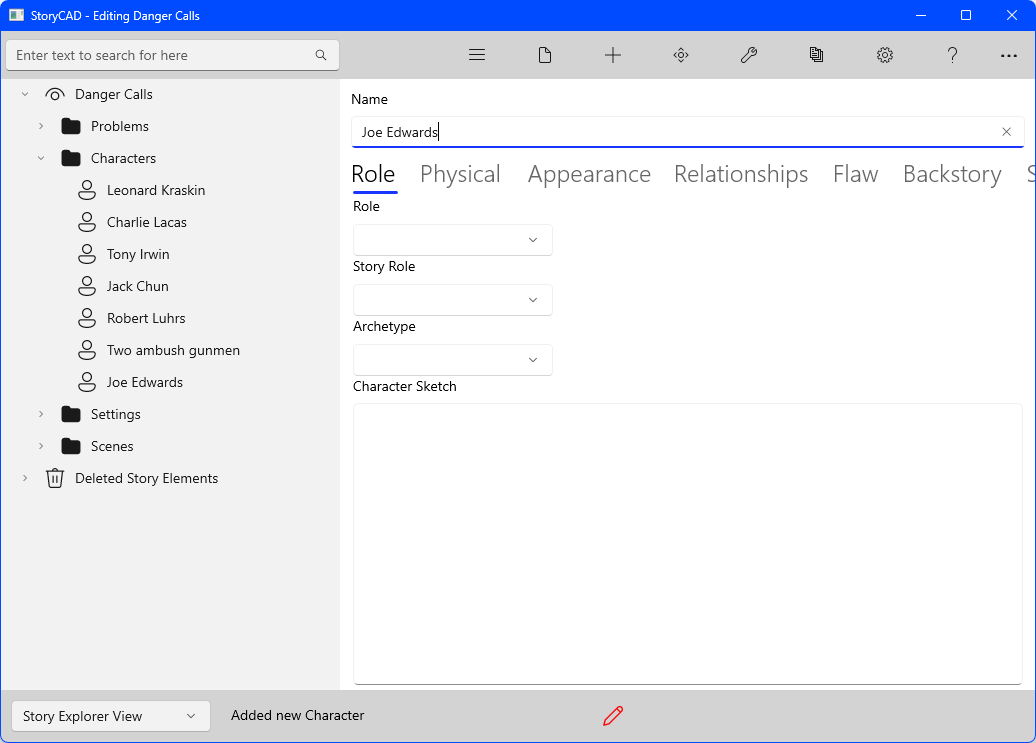

We need to figure out how the two detectives can find out where the next drug deal is to be held. One way is to enlist an ally who knows all about wireless communications. Let’s say he’s the owner of a small radio-electronics shop. But as with the interplay between Leonard and Tony, we need conflict. Let’s make this character a reluctant ally, one who’s coerced into helping our protagonists. We might make him a petty criminal of some sort, for instance, and have Leonard threaten or blackmail him. That fits Leonard’s character as we know it: he’ll go to any lengths to catch Lacas. Let’s call our new character Joe Edwards. For his crime, we need something serious enough to get him into trouble, but not too serious, or the reader will be outraged that Leonard’s left him on the street. Let’s say that he’s used his electronics skills to bug the people in the apartment where he lives; and in particular, the single woman who lives downstairs— he’s a Peeping Tom. We can also add the scene where Kraskin threatens Edwards with arrest and exposure unless he cooperates.

1

1

We’ve also gotten rid of the rest of the scaffolding plot points; we know where we’re going now and don’t need additional directions. The Dramatic Situations entry (had we used it) would have been ‘Obtaining (through force)’.

The question now turns to what Edwards will provide our detectives to enable them to eavesdrop on Lacas’ cellular phone. This is the place where some research might be useful, to make the story more believable. However, we’ll just have Edwards pull out a modified scanner and key Lacas’ phone number, which the detectives provide. This gizmo will be our detectives’ ‘listening post’ and will let them overhear anything the drug dealer says on the phone. We’ll add a plot point for this, although technically it’s a continuation of the preceding scene.

It’s vital, when plotting, to keep the readers in mind, and to think about what will keep them turning pages. This particular plot point isn’t too dramatic, but it does have appeal to curiosity. We can spice this up further by having Tony remind Lacas of the laws they’re breaking.

We’ve developed two story problems. The first or external problem is the one we just gave the reader— the setup or first act. We’ve also just resolved this problem, by giving the detectives the means to eavesdrop Lacas. The second problem, based on Leonard’s impulsiveness, has him captured by Lacas, and we’ll want the reader to know if Tony can rescue him. The second problem provides us with a complication, the capture. We could therefore look at the middle story as a way to leapfrog from the one story problem to the other. Since a story problem is a sort of story in miniature (so is a scene), plotting will frequently involve working this way; see “Plotting and the Problem form” for more details.

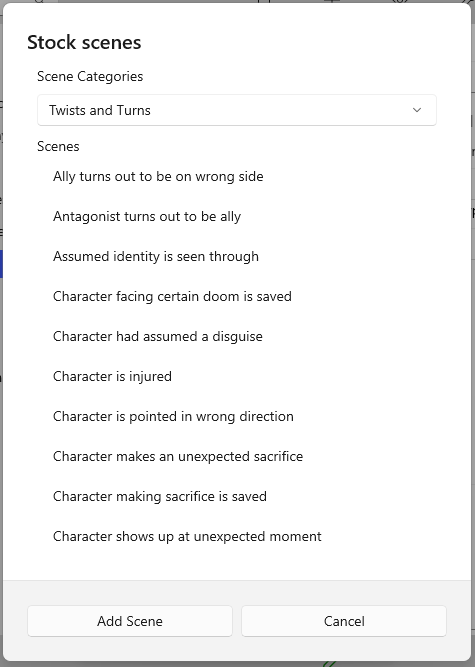

Let’s look for a way to get Leonard captured. Turning once more to the Tools menu, we select Stock Scenes from the Plotting Aids sub-menu. Several further choices appear. Let’s look at the Twists and Turns choice.

This provides us with a number of stock scenes which offer dramatic twists:

2

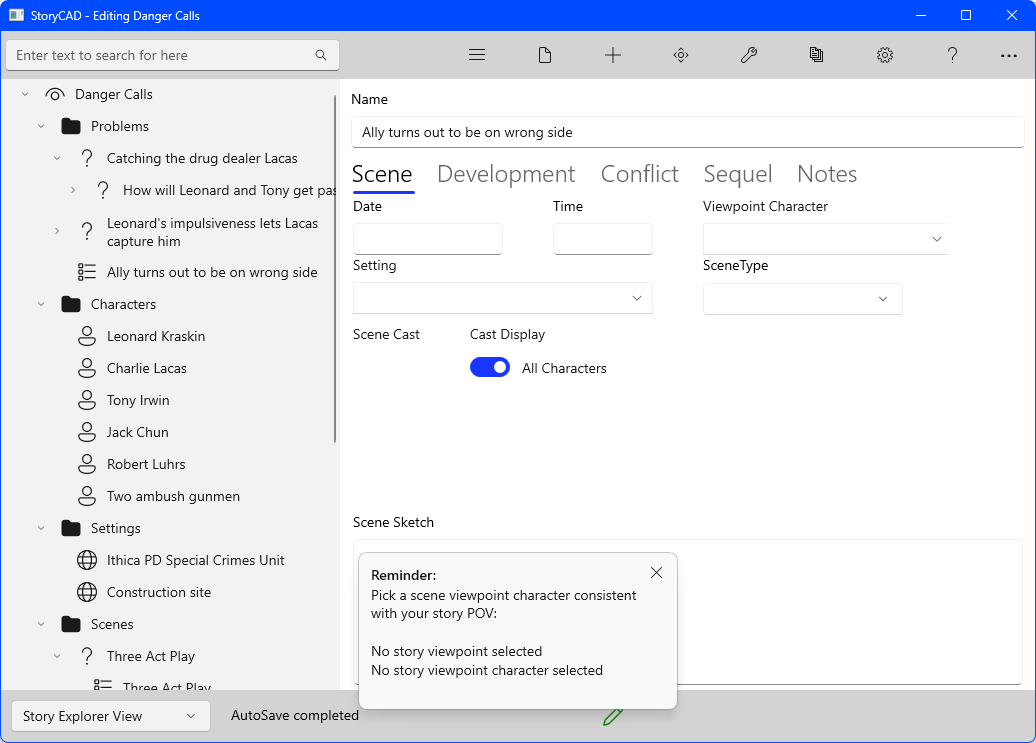

In this case the first twist listed might help us; our electronics buff ally, Joe Edwards, could be tied to Lacas in some fashion and tip him off that the two detectives are listing in on his call. Lacas could then set the cops up. We decide to go with this. Clicking on the first item in the list, and then on the Copy button, adds this stock scene into our plot outline.

3

3

We can change the scene summary to read ‘Edwards has tipped Lacas, who traps Kraskin.’

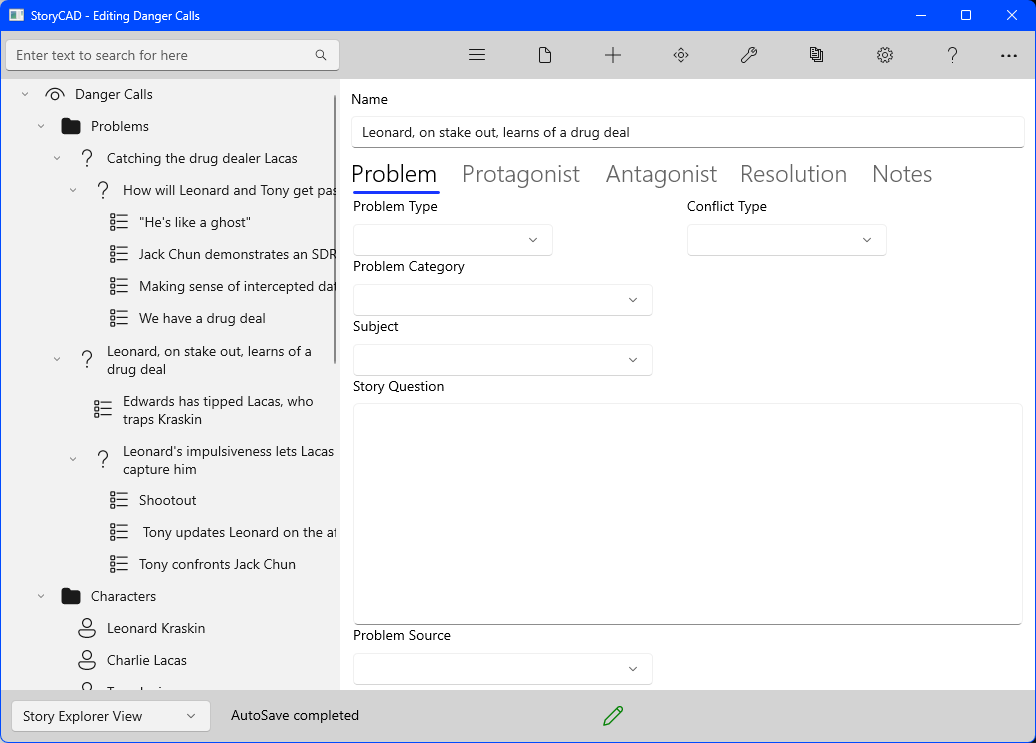

There’s something missing, a piece in which the detectives overhear the Charlie Lacas setting up a drug deal, and which leads Leonard to rush impulsively into the ambush. But why would Leonard rush to catch Lacas and leave his partner behind?

We know that our detectives are using an illegal bug to catch Lacas, so they can’t implicate their boss or other cops in their quest. It’s just the two of them. The two of them might have decided to take turns on an unoffical stake out. That way we can have Leonard working the stake out when the deal goes down.

So let’s add a plot point immediately prior to this where this takes place, and title it ‘Leonard, on stake out, learns of a drug deal .’ We can add notes to explain the details of the stake out.

Our plot outline now looks like this:

4 This is a relatively complete plot. We could sit down and start writing the story now, but that would be a mistake. There’s a lot left unfinished: we haven’t created settings, the characters are still unrefined, etc. The more these things are worked out, the richer and more complete the first draft will be when you write it.

We should evaluate our work so far. The creation of the story outline is an excellent time to review and revise. For one thing, changes at this point in the story’s development, while it’s still just an outline, are relatively cheap and easy; you’re not sacrificing prose and dialog that took time and effort to produce. There’s also another advantage: at this point you’re looking only at the structure of the story. Every story has these components of problems, characters, setting and plot; but once you begin to write, the bones will be fleshed out in narrative and dialog and dressed with your writing style. The naked structure will be, in a sense, hidden by the prose. This makes spotting and correcting structural problems more difficult.

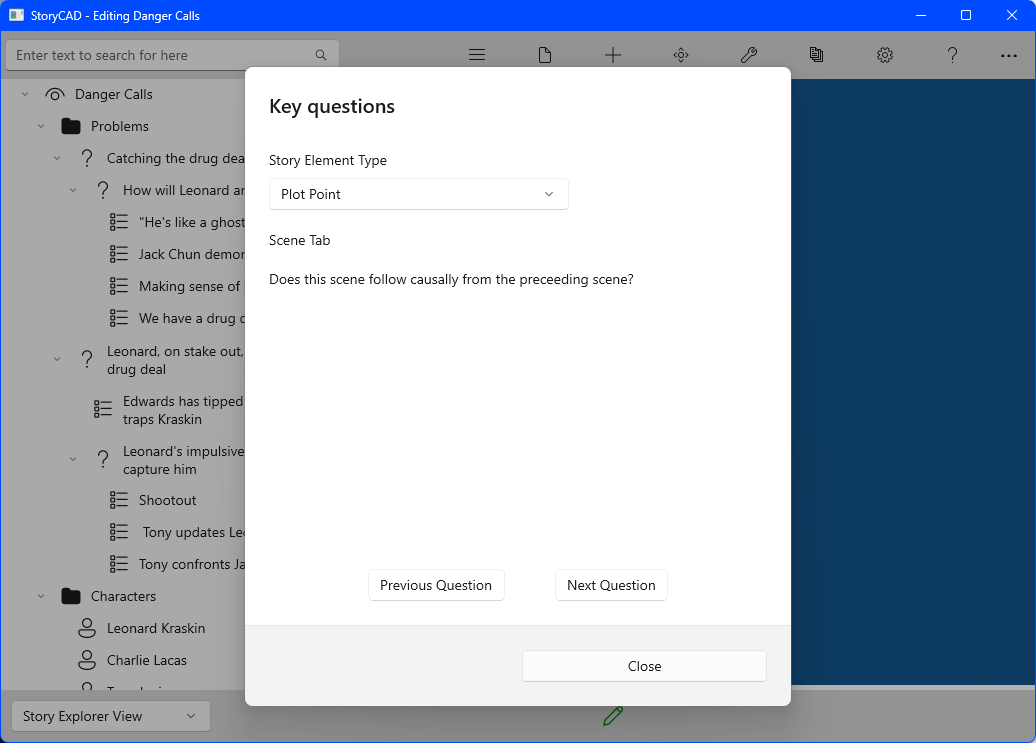

StoryCAD offers a tool, Key Questions, to assist in refining and testing your story elements. There are questions for Story, Problem, Character, Setting, and Plot. From the Tools menu, select Key Questions and then Story Questions. A form displaying a series of questions for the overall story will appear. We can test the story concept against these questions. If one is worth further study, notes can be recorded in the Answer section. For example, scrolling through the questions, we find:

5

The second part of the question is a good one; we haven’t selected a market, and therefore don’t know if the story will match slant, length requirements, etc.

It’s a good idea to use Key Questions frequently while creating the concept, and to review them before going on to the draft.

In this tutorial we’ve produced most of a story outline. We’ve worked through problem refinement, created several characters, drafted a plot, and along the way we’ve examined several tools to help these processes. The story outline was created as this tutorial was being written, exactly as shown. We feel that any story idea can be converted into a fully developed concept using these techniques.

“Danger Call” is a action-oriented suspense tale and stresses plot over character development. A character-driven story would be developed in much the same way, but the character profiles and relationships would, of course, developed more fully before developing the plot.

Previous - Creating a Story pt 8

Next - Tutorial: Creating a Story