StoryCAD

Story Idea, Concept, and Premise

Ideation

A new story outline begins with the Story Overview form. It contains:

• Story Idea

• Concept

• Premise

• Structure

The Story Overview form contains everything needed to get started, working through each of these tabs in order. Story Idea

Every story starts with an idea. The idea might come from anywhere. A conversation might lead to a bit of dialog; someone you see in a crowd could suggest an interesting character; a newspaper article or story you’re read or movie you’ve seen might spark an idea for a conflict. You’ll have more ideas than you can possibly write about, but regardless of where the idea comes from or how complete it is, at the moment of conception it’s all you have, so a good place to start is to capture the idea.

Launch StoryCAD and use Create New Story from the open menu. Change the story’s working title to something similar to its project name and simply jot down whatever notes or thoughts you have regarding the story. Idea to Concept A concept is an idea that asks a question that implies conflict. The answer to that question is what gives you your story, and it often works best if framed as a “what if” question. The Concept question should be the question the reader needs answered- it’s what propells him to read your story. Concept formulation is all about questions, and isn’t necessarily limited to just one “what if” question. In fact, a good “what if” should spark more questions. Consider Dan Brown’s The da Vinci Code for example:

What if Leonardo da Vinci implanted clues as to his views on Christianity and the veracity of scripture within his painting of “The Last Supper?”

• What if Christ didn’t die on the cross after all?

• What if the entire Christian religion is a contrivance and a deeply held secret resulting in a conspiracy?

• What if there is a highly secret group of men whose life mission is to preserve that secret?

• What if they are willing to kill to protect it?

… and so on. Another good question is “what happens?”, particularly framed as a response to your “what if” question. It’s an account of your story’s resolution. Your concept must imply conflict. To form a good concept, first ask: “What happens if this crosses that?” If you rub things together, there is going to be a fire. What happens when you bring two people together who want different things? Concept to Premise

Your Premise is the answer to the question the Concept poses.

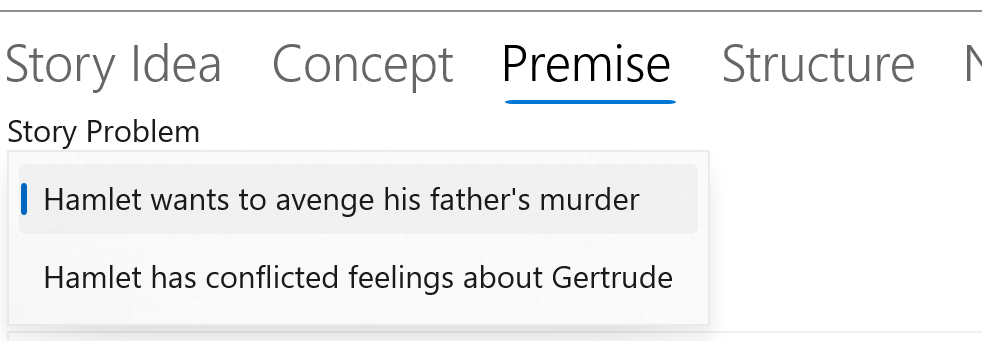

Your story can have more than one Problem story element, and every Problem has its own Premise, contained on the Resolution tab. But only one of these problems is your Story Problem, and that Problem (and its Premise) is the one you select on the Story Overview form, Premise tab:

The heart of plotted fiction is drama— a struggle in which the outcome is in doubt. Your Story Problem will lead you to understand whose problem it is (your major character), what her or she want (the goal), and what stands in their way (opposition.) The Story Problem is the wormhole you enter to understand your story.

The Story Problem has to be both difficult and urgent enough to occupy your reader from the story’s beginning to its end: in Eric Bork’s words, “One big problem it takes the whole movie to solve.” Your story isn’t over until the Story Problem is resolved.

Before you can select your Story Problem, you have to define it. You may have created your new outline using a template that gives you blank Problem story elements (External and Internal Problems or Problems and Characters). Pick one (usually the External problem), or add a new Problem, and outline it in such a way as to satisfy your concept.

Once you have created a Story Problem that seems fit, write your Premise. The premise is a condensation or synopsis of the story problem; its purpose is to be absolutely clear as to that problem and how its resolution will resolve the story. One pattern for a premise is as follows:

A character in a situation [genre, setting] wants something, which brings him into conflict with a second character [opposition]. After a series of conflicts, which are handicapped by a subplot, and after a plot twist, the final battle erupts, and character one finally resolves the conflict.

Your premise doesn’t have to be worded in this format, but it should contain these elements. Here are a couple of examples: Jaws When a fish-out-of-water, big-city cop (protagonist) moves to a small, coastal town dependent on tourism (situation), he must team with an oceanographer and a crusty sailor to convince the doubting, money-grubbing townsfolk to close their beaches because a giant, man-eating shark (opponent) is lurking just offshore, (objective) until the shark strikes (disaster), forcing the townsfolk to allow the cop and his buddies to take on the shark mano-a-mano (conflict). Star Wars A restless farm boy (situation) Luke Skywalker (the protagonist) wants nothing more than to leave home and become a Starfighter pilot so he can live up to his mysterious father (objective). But when his aunt and uncle are murdered (disaster) after purchasing renegade droids, Luke must free the droids’ beautiful owner and discover a way to stop (conflict) the evil Empire (opponent) and its apocalyptic Death Star.

Structure

[tk to be written. Discuss:

Type and Genre as setting size and expectations The importance of length Viewpoint Literary (tone, style, voice and tense) ]

Character building

Plotting

Revision

Synopsis Orthogonality: why workflow isn’t fixed / develop your own workflow

Order from Chaos: Deborah Chester’s The Fantasy Fiction Formula A sample workflow for Novels

Beginning, Middle, and End The importance of length

Problems

Problems as the core of the plot

Problems as sequences

Problem patterns

Aggregation: collecting scenes

Setting and Worldbuilding

Creating a narrative

Narrative View and why it’s distinct from Story Explorer

Braids

Previous - Workflow

Next - Problem and Character Development